By Bethany Schiffman

How can an oppressed people ever use the imposed language of their oppressor—a language created by and for the oppressor—to express their own complex reality? In her book A Small Place Antiguan author Jamaica Kincaid evokes the tragedy of this dilemma: “The language of the criminal can explain and express the deed only from the criminal’s point of view. It cannot contain the horror of the deed, the injustice of the deed, the agony, the humiliation inflicted on me.”[1] This tension is not a new issue. But the recent Black Lives Matter resurgence and renewed interest in anti-racist pedagogy make the question of how language and genre are entangled with issues of power, and how authors subvert them, even more pressing. I grapple with these questions in my dissertation focused on how Caribbean Départements d’outre mer (DOM) storytellers use oral folktales across media to create and communicate identity.

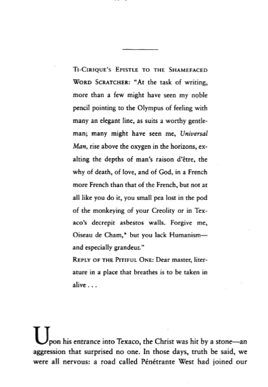

Figure 1: Martinican author Patrick Chamoiseau's hybridized language in his novel Texaco.

In their Éloge de la créolité, Caribbean creolists Jean Bernabé, Patrick Chamoiseau and Raphaël Confiant argue for a possible solution to this dilemma : « L’exigence première de l’acte littéraire [est de] savoir produire un langage au sein même de la langue » (“The first requirement of literary creation…is to be able to bring about a language within the tongue itself”).[2] In other words, in order to express what is inexpressible in the colonial tongue, creators should use their own creolized linguistic background to create a new, hybridized language. Indeed, authors from Chamoiseau to Derek Walcott to Kamau Brathwaite to dub poets are known for transgressing the colonial language by creolizing it and pushing it, forcing it to grow and change into something new.[3] But, a literary creation, or acte littéraire, does not simply engage with language; it also engages with genre.

It is no coincidence that the creolists specify a literary act. Since at least the 12th century in Europe, the written word, and eventually literature, has carried increasing importance over older, oral forms, growing in cultural capital and prestige.[4] Today literature plays a key role in Western culture, serving as a privileged space of cultural negotiation and reification of power and hegemonies. Both the colonizer’s language and the colonizer’s form carry weight in cultural identity formation. In order for a (post)colonial subject to enter into these negotiations and discussions, then, they have no choice but to use the fraught tools handed them by their subjugators. But subverting these elements can allow them to communicate their worldview, their lived experience, the horror, injustice, agony and humiliation inflicted on them.

If one possible solution to the issue language poses is to hybridize in order to create a new language, then it follows that authors can hybridize forms in order to create new genres within the old. There are many ways to do this, but one of the most obvious and most powerful is to introduce orality into the literary realm. Indeed, in systems of slavery and colonial oppression, tales, songs, and proverbs were often the only way for a people to maintain traditions and communicate without the slaver understanding. For “communities of the African diaspora…orality equals survival.”[5] At first denied access to the literary record, and then confronted with European, text-based models, postcolonial authors have had to find ways to blend their traditional orality with the powerful colonizer’s tool of literacy, to give voice to the one through the “prestige” of the other. I argue that, in so doing, postcolonial authors from around the world are able to appropriate and then subvert Western literary genres in order to express their own, individual, hybrid worldviews and experiences.

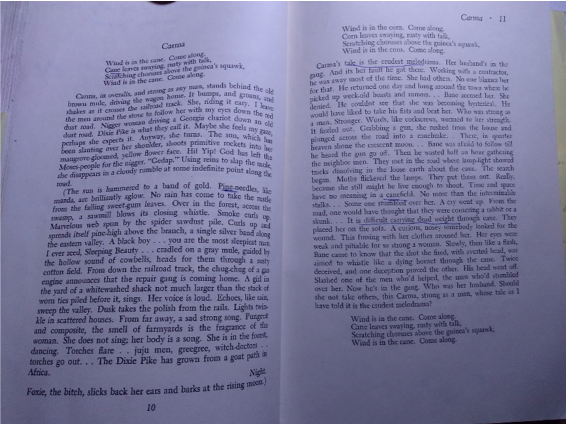

Figure 2: Hybridized language and form in Harlem Renaissance writer Jean Toomer's Cane

There are many ways to hybridize orality and literary genres. In Cane, Harlem Renaissance writer Jean Toomer intermixes poetry—or are they songs?—and prose (that one might call short stories), incorporating proverbs and tales into both, and even framing some stories with short verse (Figure 2) in ways that evoke the framing of a folktale.[6] Martinican author Aimé Césaire’s 1939 Cahier d’un retour au pays natal is formatted as a poem but reads somewhere between an ode and a rant, a poem and an essay.[7] Ghanaian author, Ama Ata Aidoo, incorporates orality into her 1966 book Our Sister Killjoy by intermixing—without line or page break—storytelling prose (“He spoke [German] well and was familiar with them in a way that made her feel uneasy. Our sister shivered and fidgeted in her chair”) with verse that seems to convey the narrator’s unedited, stream of conscious thought (“Who was Marija Sommer? / A daughter of mankind’s / Self-appointed most royal line, / The House of Aryan”), seamlessly switching between the two.[8] Even Algerian-French author Faïza Guène, writing from the Hexagon, draws heavily on orality in her novel Kiffe Kiffe Demain (itself pulled from Arabic slang meaning “same old same old”) which New York Times reviewer Lucinda Rosenfeld argues is a blend of novel, adolescent diary entries, political tract, and poetry.[9] And this list barely scratches the surface!

But what all of these texts have in common is their hybridization of genre that simultaneously subverts the colonial forms and “westernizes” the oral, creating a new form that communicates a heteroglot worldview in a packaging the privileged and powerful are open to. And now, as more and more cultural creation emerges on wiki-type sites, blogs, Facebook, YouTube, Spotify, and online, it is time to not only recognize these creolized genres, but to investigate how the influences of the 21st century are creating ever-new, ever-more-hybridized forms, and how this movement away from highly controlled forms is creating new opportunities for women and other historically-silenced groups.

Bethany Schiffman is a PhD candidate in the French and Francophone Studies Department at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Her research interests include Francophone African and Caribbean Literature and Cultures, folklore, and media studies. Her dissertation focuses on hyper-contemporary, multi-media recounting of folktales in Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Guiana and how storytellers use these stories to create and communicate individual and group identities.

Bethany Schiffman is a PhD candidate in the French and Francophone Studies Department at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Her research interests include Francophone African and Caribbean Literature and Cultures, folklore, and media studies. Her dissertation focuses on hyper-contemporary, multi-media recounting of folktales in Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Guiana and how storytellers use these stories to create and communicate individual and group identities.

[1] Kincaid, Jamaica. A Small Place (New York, N.Y.: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988), 31-32.

[2] French: Bernabé, Jean, Patrick Chamoiseau and Raphaël Confiant. Eloge de la créolité (Paris: Gallimard/Presses universitaires créoles), 1989, 46. English: Bernabé, Jean, Patrick Chamoiseau, and Raphaël Confiant. “In Praise of Creoleness.” Translated by Mohamed B. Taleb Khyar. Callaloo 13, no. 4 (1990): 900. https://doi.org/10.2307/2931390.

[3] Knepper, Wendy. Patrick Chamoiseau: A Critical Introduction (Jackson, M.S.: UP of Mississippi, 2012), 64-65.

[4] Vitz, Evelyn Birge. Orality and Performance in Early French Romance (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1999), ix & 44.

[5] Chancy, Myriam J.A. Framing Silence: Revolutionary Novels by Haitian Women (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers UP, 1997), 74.

[6] Toomer, Jean. Cane (New York, N.Y.: Liveright, 1975).

[7] Césaire, Aimé. Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (Paris Présence Africaine, 1983).

[8] Aidoo, Ama Ata. Our Sister Killjoy (Harlow: Longman Group, 1977), 9, 48.

[9] Kelleher, Fatimah. “An Interview with Faïza Guène.” Wasafiri 28, no. 4 (December 1, 2013): 3. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690055.2013.826783; Rosenfeld, Lucinda. “Catcher in the Rue.” The New York Times, July 23, 2006, sec. Books. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/23/books/review/23rosenfeld.html.