By Viviana Pezzullo

In the last decades, Francophone Caribbean Studies have increasingly focused on the issues of gender and language independently, however, these two topics have rarely been brought together to enhance our understanding of sociolinguistic power dynamics within Caribbean literature and culture. The relationship between Creole and French is often at the heart of a debate revolving around hierarchy in terms of racial, cultural, and social domination, disregarding the role that gender–with its implications in access to education and employment–plays in it.

For this reason, it is fundamental for scholars interested in conducting linguistic research or studying the interplay of language, transnational identity, and gender in the Francophone Caribbean, to reclaim the importance of Dany Bébel-Gisler. Her theoretical scholarship about Creole is as groundbreaking as the work of the Créolité group, but far less studied.

Dany Bébel-Gisler was a Guadeloupean author and sociolinguist who was born in Pointe-à-Pitre on April 7, 1935 and died in Lamentin on September 28, 2003. Her grandfather was a sugarcane plantation owner and her father married a mulatresse who was a worker on the family plantation. At a young age, Bébel-Gisler moved to Toulouse for the classes préparatoires, and she was awarded the Prix Spécial de français, which allowed her to attend the École Normale Supérieure de Paris. While she started her degree with a focus on literary studies, her interest shifted towards linguistics, sociology, and ethnography. Her doctoral dissertation on the status of Creole in the Antilles was published in 1976 by L’Harmattan with the title La langue créole, force jugulée: étude socio-linguistique des rapports de force entre le créole et le français aux Antilles.

Dany Bébel-Gisler was a Guadeloupean author and sociolinguist who was born in Pointe-à-Pitre on April 7, 1935 and died in Lamentin on September 28, 2003. Her grandfather was a sugarcane plantation owner and her father married a mulatresse who was a worker on the family plantation. At a young age, Bébel-Gisler moved to Toulouse for the classes préparatoires, and she was awarded the Prix Spécial de français, which allowed her to attend the École Normale Supérieure de Paris. While she started her degree with a focus on literary studies, her interest shifted towards linguistics, sociology, and ethnography. Her doctoral dissertation on the status of Creole in the Antilles was published in 1976 by L’Harmattan with the title La langue créole, force jugulée: étude socio-linguistique des rapports de force entre le créole et le français aux Antilles.

As scholar James Arnold has argued, Bébel-Gisler was not interested in Creole as a code for a limited circle of intellectuals, therefore, distancing herself from the Créolité group. Her approach was more pragmatic and aimed to introduce Creole in school curricula, promoting a writing system specific to Guadeloupean Creole, which she proposes in Kèk prinsip pou ékri kréyól (1975). Bébel-Gisler’s passion for education and pedagogy is grounded in her own teaching practice, which she developed through tutoring children of African and Algerian immigrant workers in Nanterre and Aubervilliers in the 1960s. In most cases, these pupils did not speak French, so this experience heavily informed her research and led her to explore teaching Creole and French as a Second Language, within marginalized communities. With this intent, in 1979, Bébel-Gisler founded the Centre d’Education Populaire Bwadoubout, where students from underprivileged households could study and where Creole was the primary language of instruction.

In Bébel-Gisler’s work, Creole is both the object of sociolinguistic research, but also the pillar of her militant activism; Creole is that “cordon ombilical qui nous relie à l’Afrique, aux autres, à nous mêmes” (Le défi culturel 23) [umbilical cord that connects us to Africa, to others, to ourselves]. Language as a way to express identity also becomes a key element of nationalistic rhetoric and demands during the Guadeloupen independentist movement of the 1970s and 1980s against French hegemony: “c’est tout ça qui nous à fabriqués, nous, Guadeloupéens” (Léonora 79) [this is what created us, us Guadeloupean]. Through her analysis of the use of Creole, Bébel-Gisler digs into the herstory of Guadeloupe, a past of colonization that for the most part remained “buried,” overshadowed by colonial history.

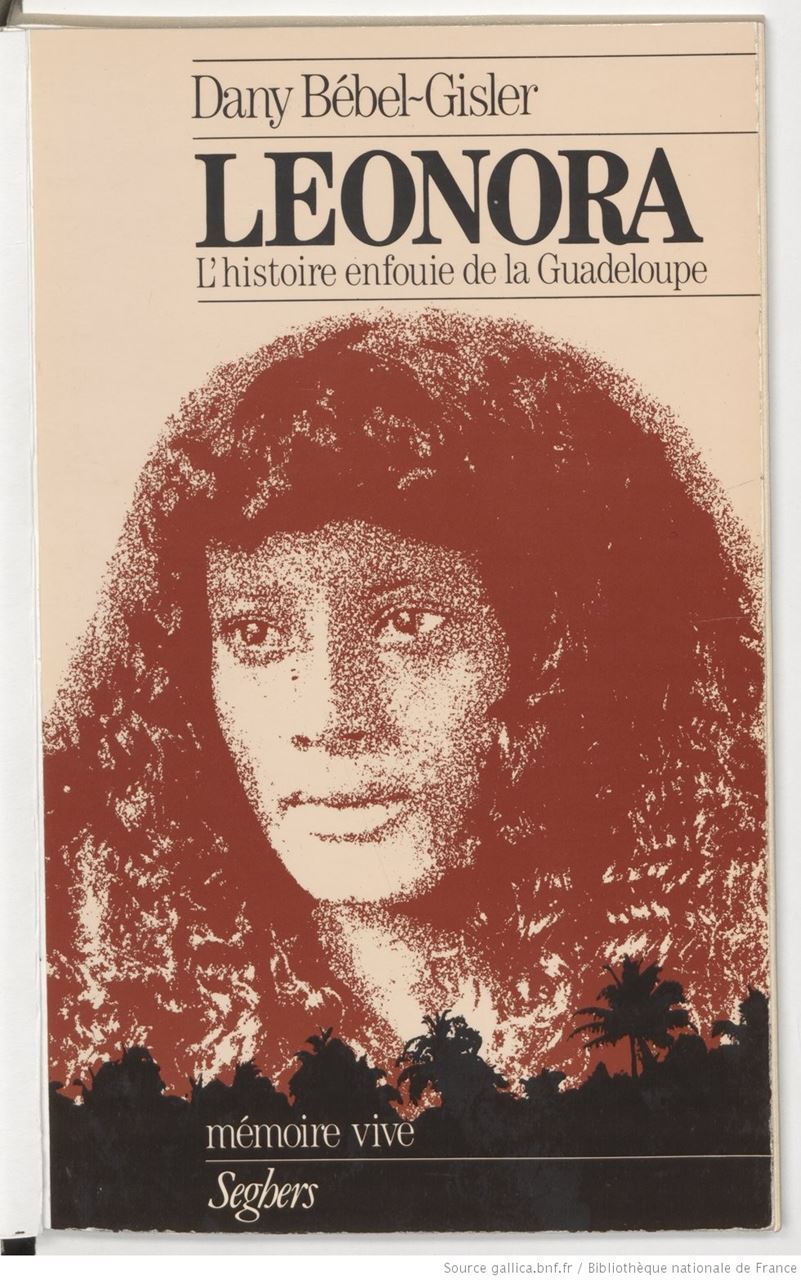

Her project of shedding light on Guadeloupean past becomes imperative in Léonora: l’histoire enfouie de la Guadeloupe (1985), probably Bébel-Gisler’s most famous work. Léonora offers slices of life in Guadeloupe while painting a picture of its linguistic habits through the narrative of Léonora–an 80-year-old attacheuse from Lamentin. During a series of interviews, conducted in the late 1970s and early 1980s (hence in the middle of Guadeloupe’s nationalistic movements), Bébel-Gisler collected and transcribed Léonora’s words, who becomes the spokesperson of her community. While Bébel-Gisler herself defines the book as a novel, scholars Vera M. Kutzinki and Cynthia Mesh-Ferguson underscore how this is a prime example of the Latin-American genre of testimonio in the French language. The testimonial value as well as the sociolinguistic complexity of Léonora, makes it a suitable source for all sorts of interdisciplinary research, ranging from linguistics to literary studies, through postcolonial history and world politics.

Her project of shedding light on Guadeloupean past becomes imperative in Léonora: l’histoire enfouie de la Guadeloupe (1985), probably Bébel-Gisler’s most famous work. Léonora offers slices of life in Guadeloupe while painting a picture of its linguistic habits through the narrative of Léonora–an 80-year-old attacheuse from Lamentin. During a series of interviews, conducted in the late 1970s and early 1980s (hence in the middle of Guadeloupe’s nationalistic movements), Bébel-Gisler collected and transcribed Léonora’s words, who becomes the spokesperson of her community. While Bébel-Gisler herself defines the book as a novel, scholars Vera M. Kutzinki and Cynthia Mesh-Ferguson underscore how this is a prime example of the Latin-American genre of testimonio in the French language. The testimonial value as well as the sociolinguistic complexity of Léonora, makes it a suitable source for all sorts of interdisciplinary research, ranging from linguistics to literary studies, through postcolonial history and world politics.

Léonora is a prime example of how linguistic habits reveal a lot about women’s living conditions and ongoing power dynamics in the Francophone Caribbean. In this context, the dichotomy between French and Creole must be reconsidered in the light gender, taking into account the fact that women tend to rely much more on French as opposed to Creole. In Léonora’s words scholars find literary evidence of what sociolinguist Ellen Schnepel writes about linguistic habits of women in the Francophone Caribbean: “the quest for group identity and linguistic rights conflicts with basic material needs—such as education, jobs, and economic security” (213).

Further research about Bébel-Gisler’s contribution to Francophone literature and theory is very much needed. Indeed, while Bébel-Gisler is often remembered solely in the context of defining transnational identity or discussing the role of Creole in the schooling system, her works contribute greatly to our understanding of gender, language and power dynamics in the Francophone Caribbean. Her research and theoretical framework not only complement works by Simone Schwarz-Bart and Gisèle Pineau, but also shed a new light on studies about the Créolité. Rediscovering Bébel-Gisler will allow scholars to engage with all sorts of interdisciplinary research, ranging from linguistics to literary studies, through postcolonial history and world politics.

Further Reading

Primary Sources

Bébel-Gisler, Dany.Cultures et pouvoir dans la Caraïbe: langue créole, vaudou, sectes religieuses en Guadeloupe et en Haïti. L’Harmattan, 1975.

--.La langue créole, force jugulée: étude socio-linguistique des rapports de force entre le créole et le français aux Antilles. L’Harmattan, 1976.

--.Léonora: l’histoire enfouie de la Guadeloupe. Seghers, 1985.

--.Le défi culturel guadeloupéen: devenir ce que nous sommes.Éditions caribéennes, 1989.

Secondary Sources

Arnold, A. James. “The Erotics of Colonialism in Contemporary French West Indian Literary Culture.”New West Indian Guide, vol. 68, no. 1-2, Jan. 1994, pp. 5–22.

Kelley, Barbro Lucka. “The Poetics of Nationalism in Dany Bebel-Gisler’s Leonora.”Revista Mexicana del Caribe, vol. 6, 1998, pp. 2018-230.

Kutzinki, Vera M., and Cynthia Mesh-Ferguson.Afterword.Leonora: The Buried Story of Guadeloupe, by Dany Bébel-Gisler. 1985. Translated by Andrea Leskes, University Press of Virginia, 1994, pp. 261-278.

Malena, Anne. “Leonora: The Making of the Self.”The Negotiated Self: The Dynamics of Identity in Francophone Caribbean Narrative. Peter Lang, 1999, pp. 27-65.

Mesh, Cynthia J. “Empowering the Mother Tongue: The Creole Movement in Guadeloupe.” In Springfield, Consuelo López, ed.Daughters of Caliban: Caribbean Women in the Twentieth Century. Indiana University Press, 1997, pp. 2-38.

Santiago, Frances J. “Bebel-Gisler, Dany (1935-2003).” In Knight, Franklin W., and Henry Louis Gates, eds.Dictionary of Caribbean and Afro-Latin American Biography. Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. 275-276.

Schnepel, Ellen M. “The Other Tongue, the Other Voice: Language and Gender in the French Caribbean.” Language and Social Identity. Edited by Richard K. Blot. Praeger, 2003, pp. 199-224.

Viviana Pezzullo is a Ph.D. Candidate in Comparative Studies (French, Francophone Caribbean, and Italian) at Florida Atlantic University. Her research interests include 20th- and 21st-centuries literature and culture (with a particular emphasis on women writers), visual arts, translation, and digital humanities. She has published in The French Review, and her article on Christine de Pizan’s protofeminist translation of Boccaccio is forthcoming in 2021 in NeMLA Italian Studies.

Viviana Pezzullo is a Ph.D. Candidate in Comparative Studies (French, Francophone Caribbean, and Italian) at Florida Atlantic University. Her research interests include 20th- and 21st-centuries literature and culture (with a particular emphasis on women writers), visual arts, translation, and digital humanities. She has published in The French Review, and her article on Christine de Pizan’s protofeminist translation of Boccaccio is forthcoming in 2021 in NeMLA Italian Studies.