By Katherine Hammitt

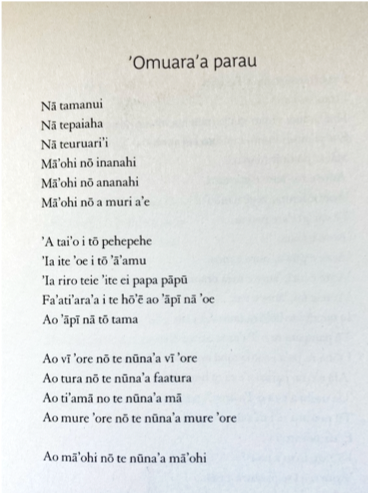

First section of L'île des rêves écrasés, Chantal Spitz (1991)

From the first page of Chantal Spitz’s 1991 novel L’île des rêves écrasés, it is clear this work will defy expectations. This text, lauded as the first francophone novel by a Tahitian author, immediately confronts the reader with five pages of verse written in Reo Tahiti, an autochthonous language of the French overseas collective Te Ao Mā’ohi, or French Polynesia. Neither translated nor summarized, these initial pages set the scene for more than the story to unfold; from the beginning, this novel challenges the reader’s understanding of the islands and the continued marginalization of Polynesian voices.

It is a challenge characteristic of the author’s work and of the work that francophone authors are doing across Oceania. Though the francophone spaces of the Pacific Ocean are underrepresented in francophone literary and postcolonial studies, they are the site of abundant literary and critical production. As francophone studies reaches for new ways of imagining transcolonial solidarities, francophone Oceania fosters connection and collaboration across thousands of miles of water. While literary works from Te Ao Mā’ohi/French Polynesia and Kanaky/New Caledonia are as diverse as the communities in which they are produced, writers like Ari’irau, Claudine Jacques, Nicolas Kurtovitch, Titaua Peu, Déwé Gorodé, and, of course, Chantal Spitz are engaged with producing stories that defy Western literary conventions and celebrate the continuation of their own rich literary tradition.

Chantal Spitz is arguably the most well-known author from the region. Beyond her status as the first Tahitian writer to publish a novel, she is a central figure in her literary community. In 2002, she cofounded Littérama’ohi, a literary journal that publishes works from writers across Oceania. The journal is dedicated to fostering literary connections within French Polynesia and to promoting Polynesian voices. She is a frequent speaker at conferences and literary festivals, such as Lire en Polynésie, which has just concluded its 20th annual salon du livre (this year entirely online). An outspoken proponent of independence from France, Spitz has published several critical articles and a collection of political and personal essays, Pensées insolentes et inutiles (2006). Her literary work is no less political. In addition to L’île des rêves écrasés, Spitz has written two other novels, Hombo, transcription d’une biographie (2002) and Elles, terre d’enfance (2011), as well as Cartes postales, (2015), a collection of short vignettes.

Chantal Spitz is arguably the most well-known author from the region. Beyond her status as the first Tahitian writer to publish a novel, she is a central figure in her literary community. In 2002, she cofounded Littérama’ohi, a literary journal that publishes works from writers across Oceania. The journal is dedicated to fostering literary connections within French Polynesia and to promoting Polynesian voices. She is a frequent speaker at conferences and literary festivals, such as Lire en Polynésie, which has just concluded its 20th annual salon du livre (this year entirely online). An outspoken proponent of independence from France, Spitz has published several critical articles and a collection of political and personal essays, Pensées insolentes et inutiles (2006). Her literary work is no less political. In addition to L’île des rêves écrasés, Spitz has written two other novels, Hombo, transcription d’une biographie (2002) and Elles, terre d’enfance (2011), as well as Cartes postales, (2015), a collection of short vignettes.

Spitz’s writing is characterized by her commitment to promoting Polynesian voices, often as she highlights their historical marginalization. In the epigraph to Pensées insolentes et inutiles, Spitz writes,

j’écris ce que j’ai envie d’écrire

dans l’illusion d’écrire de ma propre voix

dans une vaine tentative d’indépendance

face à une société peureuse

comme un constant exil

Spitz writes against this estrangement from her own voice, both within the content of the narratives she tells and in the form of her writing. In L’île des rêves écrasés, Spitz emphasizes the contrast between Tahitian and French languages, underlining the ecological violence depicted in the story with the linguistic violence inherent in French Polynesia’s colonial relationship with France. Cartes postales confronts the Edenic image of Tahiti by portraying a reality of extreme, everyday violence, captured in seven vignettes told from the perspective of locals on the Polynesian island. Spitz’s writing defies Western conventions of genre, weaving verse in with prose, and even abandoning punctuation and capitalization. Her lyrical style is a commitment to the oral form, a continuation of the rich oral tradition across Oceania. It is a further resistance to ontological violence against Polynesian literary production, undermining the false, Western dichotomy of written vs. oral by embracing the productive merging of the two forms.

Spitz is undoubtedly a central figure of the literary community in francophone Oceania, her work a cornerstone of the canon. But the breadth of literary production in the region defies brief summation. It is a diverse canon whose authors are each in their own way committed to the promotion of marginalized voices and defying expectations.

![]()

Primary sources:

Spitz, Chantal. Cartes postales: nouvelles. Papeete: Au Vent des Îles, 2015.

——. Elles, terre d’enfance, roman à deux encres. Papeete: Au Vent des Îles, 2011.

——. L’Ile des rêves écrasés. Papeete: Au Vent des Îles, 2003 (originally published in 1991 by

Éditions de la plage) .

——. Pensées insolentes et inutiles. Papeeté: Te ite, 2006.

Further reading:

Anderson, Jean. “Translating Chantal Spitz: Challenges of the Transgeneric Text.” Autralian

Journal of French Studies. Liverpool Vol. 50 Iss. 2 (May-Aug 2013): 177-188.

Devatine, Flora. Tergiversations et Rêveries de l’Ecriture Orale: Te Pahu a Hono’ura. Papeete:

Au Vent des Îles, 1998.

Frengs, Julia L. Corporeal Archipelagos: Writing the Body in Francophone Oceanian Women’s

Literature. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2018.

Margueron, Daniel. Flots d’encre sur Tahiti: 250 ans de littérature francophone en Polynésie

française. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2015.

Ramsay, Raylene. The Literatures of the French Pacific: Reconfiguring Hybridity. Liverpool:

Liverpool University Press, 2014.

Katherine Hammitt is a PhD Candidate in Comparative Studies in Literature and Culture (French and Francophone Studies) at the University of Southern California. Her dissertation project, tentatively titled Beyond the Sea that Separates, engages with women francophone writers of Oceania. Her research interests include postcolonial theory, visual culture, women writers, and memory studies.

Katherine Hammitt is a PhD Candidate in Comparative Studies in Literature and Culture (French and Francophone Studies) at the University of Southern California. Her dissertation project, tentatively titled Beyond the Sea that Separates, engages with women francophone writers of Oceania. Her research interests include postcolonial theory, visual culture, women writers, and memory studies.